Can AI Rescue Us from the Mess of Prior Auth?

Yes, But It’ll Take More Than Putting Lipstick on Today’s Pig of a System

I’ll begin with as unfashionable a statement as I can imagine uttering in 2025: I don’t think there’s anything fundamentally wrong with requiring prior authorizations for certain medical tests, procedures, and therapies.

Before your blood begins to boil, let me quickly add this: I think there is everything wrong with how prior auth works today.

To me, the question is not, “Should prior auth go away completely?” It can’t and it won’t. Rather, the question should be, “Can prior auth be made more ethical and less infuriating?” I believe it can, and that AI can help. But it will require a rethinking of the entire process.

Today’s Prior Auth

Prior auth is the system by which the payer (generally an insurance plan, but sometimes a healthcare delivery organization accountable for the cost of care) sets and enforces standards to be met before agreeing to pay for a medication, test, or procedure. Prior auth requirements exploded with the growing popularity of Medicare Advantage (MA), the federal program in which patients’ Medicare benefits are turned over to a health plan, creating an arrangement known as capitation in which the health plan receives a fixed sum (adjusted for patient age and preexisting illnesses) to care for a patient, usually over a full year. Such arrangements give health plans a powerful incentive to minimize their expenditures. (The plans, of course, would say their incentive is to encourage the delivery of appropriate, evidence-based care.) Today, more than half of Americans over 65 are enrolled in Medicare Advantage, up from 17 percent a decade ago.

With its growing application in MA, prior auth has become the policy everybody – on both sides of the Red/Blue divide – loves to hate, a sentiment that became disturbingly clear with the vitriolic reactions to the 2024 murder of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson. In one of their few areas of agreement, both the Biden and Trump administrations have been aggressive in cracking down on prior auth. In 2024, Biden issued a federal rule that, beginning in 2026, will halve the time in which health insurers must respond to prior auth requests, from 14 days to 7; expedited requests require an answer within 72 hours. Insurers also need to provide reasons for denying a request and publicly report metrics like the percentage of denials. During his Senate confirmation hearings to become director of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Mehmet Oz called prior auth “a pox on the system” and promised further reforms, many based on AI. Since taking office, Trump and team have received voluntary commitments from major insurers to limit the scope of services requiring prior auth, standardize electronic submissions, and more.

AI to the Rescue?

Physicians complain bitterly about prior auth, for good reason. For every physician in an office practice, the doctor and staff spend an average of twelve hours a week submitting prior auth requests. Physicians consider the process soul-crushing and often harmful to their patients, by either delaying needed care or sometimes blocking it altogether. For years, doctors have been desperate for a tool to help them do battle with the insurance companies.

AI entered the prior auth wars soon after the public release of ChatGPT in November 2022. Within weeks, Doximity, which describes itself as LinkedIn for physicians, rolled out a prior auth request generator. “All you had to do was type the letter ‘O’ and it automatically created a prior auth for Ozempic [the weight loss drug], addressed to UnitedHealthcare,” Doximity CEO Jeff Tangney told me, with a mix of amusement and awe. Today, tens of thousands of physicians use Doximity’s prior auth tool, noting that it not only saves time but, by pulling in key patient data from the electronic health record, markedly cuts their denial rate.

Of course, the insurance companies responded in kind, deploying their own AI to review – and often reject – doctors’ AI-generated prior auth requests. We quickly found ourselves in a ludicrous prior auth arms race, with AI serving as the primary weapon on both sides.

Insurance companies and health plans also began using AI to deny other forms of care. A series in STAT in 2023 chronicled the use of AI by NaviHealth, a now-defunct UnitedHealth subsidiary, to deny coverage for skilled nursing and other care. “They are looking at our patients in terms of their statistics. They’re not looking at the patients that we see,” said one frustrated nursing home leader. A hospice medical director noted that many of his patients were forced into appeals that would take far longer than the patients were expected to live. “The appeal outlasts the beneficiary,” said the director.

Dealing with the bureaucratic miasma of prior auth sometimes involves more than the generation of a written authorization request. One start-up, Infinitus Systems, built an AI program to automate the process of calls to the insurance company for authorization. Basically, the bot twiddles its digital thumbs during the on-hold period, then signals the clinic staff when a human from the insurance company picks up the phone. Just take that in for a second: A solution that mostly serves as an automated on-hold Task-Rabbit has raised more than $100 million in venture funding. That fact alone should give you a sense of how desperate health systems and physicians are to slice through the Gordian knot of prior auth.

Medicare’s Surprising Prior Auth Move

Given this bipartisan antipathy, I was surprised last month to hear of Medicare’s intention to launch a pilot program to expand the use of prior auth to the shrinking number of elderly patients who have chosen to stay in traditional fee-for-service Medicare. The program, whose official title is “The Wasteful and Inappropriate Service Reduction” (WISeR) Model pilot, will initially focus on a small group of procedures that Medicare has deemed “vulnerable” to overuse, fraud, and abuse: knee arthroscopy, electrical nerve stimulation implants, and skin substitutions for wound healing. Starting in January, the program will be rolled out in six states: Arizona, New Jersey, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas, and Washington.

Where does AI fit in? According to the plans for the pilot, AI will perform a first-pass review to help determine whether Medicare should pay for a given intervention, and the AI companies involved in the program will be compensated in part based on the savings they generate by rejecting claims. In an effort to reassure those worried about having an AI bot nix grandma’s arthroscopy, Medicare vowed that final rejection decisions will be made by licensed clinicians.

The reaction to the new Medicare program was swift and overwhelmingly negative. “I’m concerned that this AI model will result in denials of lifesaving care and incentivize companies to restrict care,” House Energy and Commerce Committee ranking member Frank Pallone (D-N.J.) said last week in a House subcommittee hearing. “It’s been referred to as the AI death panel,” added Rep. Greg Landsman, an Ohio democrat whose state will be part of the pilot. (Note the skillful use of the Trumpy “people are saying” rhetorical device.) “You get more money if you’re that AI tech company if you deny more claims. That is going to lead to people getting hurt.”

The backlash against the new Medicare pilot was unsurprising, given that the program mixes prior auth (a process that no one trusts), applied by AI companies (that no one trusts) operating under a bounty system (which no one trusts). Stanford law professor Michelle Mello, an expert in health law, testified at that same House subcommittee hearing. She took a middle ground, saying that while the new program might help contain costs, it’s currently unclear how well AI will do in handling prior auth requests. “We have pretty good evidence that prior authorization as a process itself is fraught,” Mello said. “We don’t know, because there’s no publicly available information that would enable someone like me to be able to tell you, ‘Does using AI make prior authorization better for patients or worse?’ Because I think both outcomes are very possible.”

Rethinking Prior Auth in an AI World

For clinicians and patients alike, a world without prior auth seems blissful, but it’s not in the cards. There are simply too many examples of patients being subjected to expensive tests and treatments completely unsupported by evidence. Moreover, there are appalling (and to most physicians, embarrassing) examples of fraud and abuse. Just read this scandalous story about skin substitutes or my wife Katie Hafner’s exposé of Mohs surgery abuses in private equity-owned dermatology practices and try to defend the notion that there should be no oversight or accountability of any physician’s decision regarding any test or procedure, particularly when the program in question – Medicare – is funded by tax dollars and on the brink of insolvency.

So the real question is how to create a prior auth process that is fair, limited in scope, efficient, and acceptable to both patients and clinicians.

Unfortunately, the solution won’t come through sprinkling some AI fairy dust onto today’s massively broken system. While having AI draft prior auth requests certainly helps decrease the burden on physicians and their practices, it’s just lipstick on a very homely pig. To reimagine prior auth, we need to think about automating the entire process, starting with connecting the payer to the provider’s electronic health record. The ability of large language models to review clinical notes (i.e., to read unstructured data) means that such EHR-centered reviews can now serve as the core of prior auth decisions, replacing today’s system of ping-ponging faxes.

What would this look like? In response to a physician’s order for a limited number of prior-auth-requiring medications, tests, or procedures, the insurer would perform an AI-enabled review of the chart to see if the patient meets the criteria. If the answer is no, such a system could smooth – and perhaps automate – the process by which the clinician provides evidence supporting her choice.

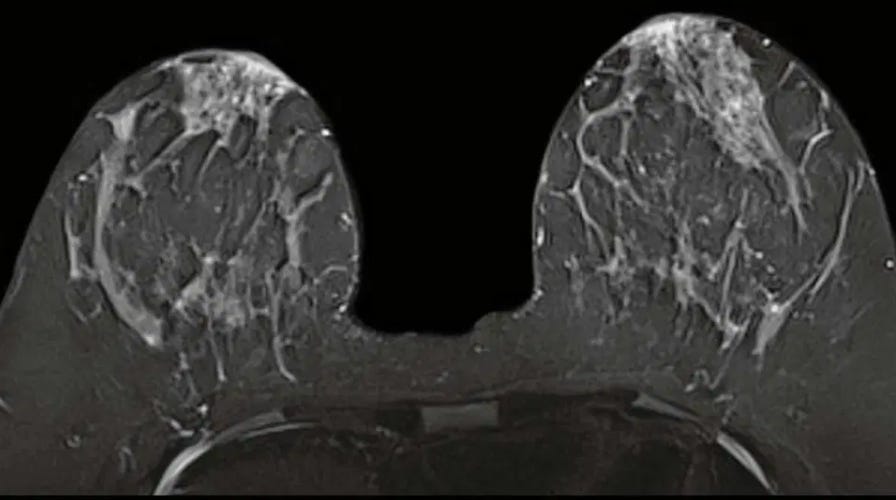

For example, imagine that a clinician has ordered a breast MRI for a patient with dense breasts, for which standard mammograms are notoriously unreliable. In today’s system, the physician or her staff would need to write up a prior auth request, manually enter the relevant patient history and prior testing information, fax the form to the insurance company, and wait a week or two for an answer.

Now consider a future system in which AI-infused prior authorization was integrated into the EHR. If the insurer’s criteria for approving the MRI included a prior mammogram showing dense breasts and limited interpretability – and let’s be sure we continue to have humans with both content knowledge and a functioning ethical compass setting these criteria – the AI would review the chart looking for evidence of that test and the radiologist’s interpretation. Failing to find it, the system would ask for such documentation, and, if none were available, automatically “tee up” a mammogram order directly in the EHR for the physician to consider. The process could be completed in minutes.

While this level of connectivity and AI-fueled analytics would improve matters, there would undoubtedly be privacy and business concerns stemming from such arrangements, and some challenging work would need to be done to create appropriate rules of engagement. These rules should include a requirement that those requests flagged by AI as potentially inappropriate be reviewed by a qualified clinician before a final rejection is issued.

AI might also be used to help target those procedures – and physicians – that require scrutiny, and those that don’t. I’m encouraged by Medicare’s decision to begin its pilot program with a small number of procedures that truly are subject to overuse and abuse. Even if we manage to construct a prior authorization system with far less friction than today’s, prior auth should be limited to high-cost or high-risk items for which there’s clear evidence of widespread inappropriate use.

In terms of the providers, one can also imagine an AI system that, after approving a certain number of tests, procedures, or medication orders by a given clinician, would deem the provider to be sufficiently trustworthy to be exempted from prior auth. Such trusted entity programs are used in many industries, like TSA’s Trusted Traveler program and “Certified Supplier Programs” in manufacturing.

Early Signs of Progress

Some health systems and payers are beginning to implement these types of automated, EHR-based, AI-enabled solutions. Louisiana-based Ochsner Health has connected its EHR to the computer systems of its largest insurers and now receives instant approvals for about half the requests on a select group of procedures. Even when an approval isn’t instantaneous, the link has sped up the process – often shortening the time from appeal to decision from days to hours.

And Elevance, the health plan formerly known as Anthem, has partnered with Montefiore, a Bronx-based health system, to connect the insurer to the health system using Epic’s Payer Platform, a recently launched feature of Epic’s EHR designed to automate the exchange of data between clinical providers and payers. Many of the denials in the past were issued because Elevance didn’t have the information it needed to approve the request. Elevance claims that this EHR-based link has reduced these denials by 76 percent.

While the current processes are beginning to take advantage of relatively basic search tools and algorithms, one can imagine even more expansive roles for AI. In a 2023 article, physician-informaticist Leslie Lenert and colleagues suggested the use of a panel of AI-simulated virtual experts to adjudicate requests for treatments or tests in areas that lack evidence-based guidelines.

All these interventions would need to be thoroughly vetted and tested, as the opportunities for unintended consequences and overreach are substantial. It won't take much for patients and clinicians to lose trust in a system that appears to simply amplify insurance companies’ ability to prioritize financial considerations over patient-centered care. However, given how fundamentally broken the current prior auth system is – with its delays, administrative burdens, and arbitrary denials – I remain cautiously optimistic that a thoughtfully implemented, EHR-embedded, AI-enhanced system could represent a meaningful improvement over the status quo, provided it includes strong safeguards and genuine accountability measures.

Let’s Fix It

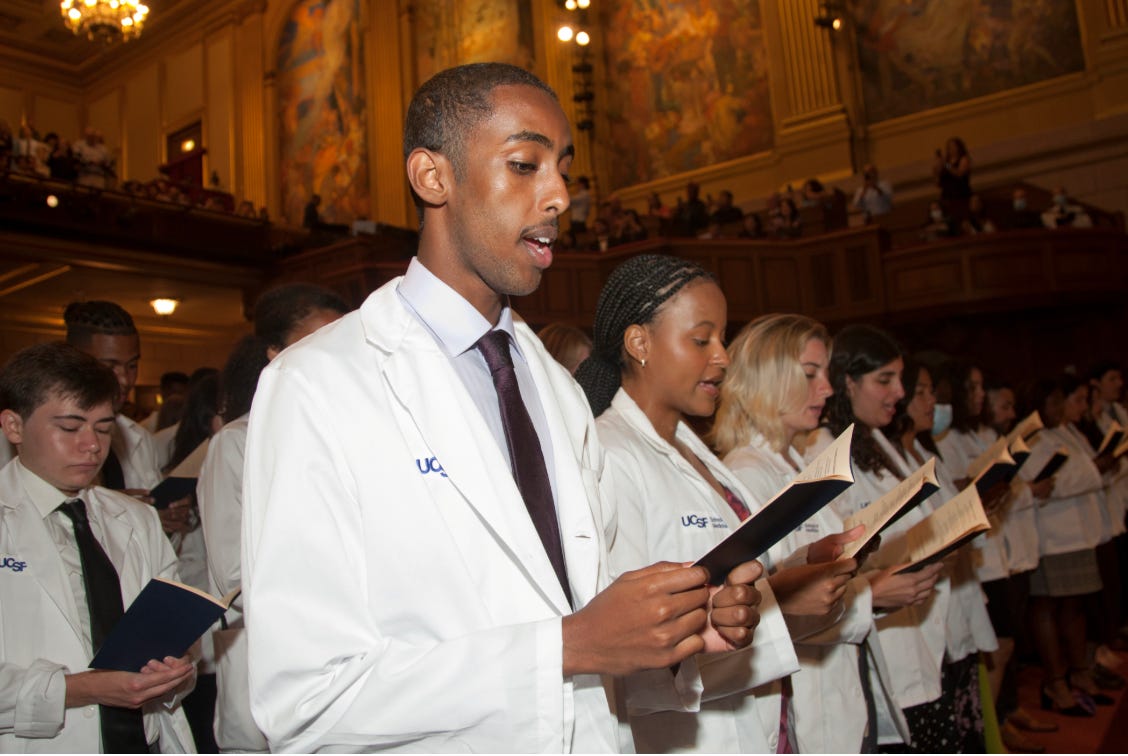

Don’t get me wrong: in a head-to-head, who-do-you-trust contest between a physician who has taken the Hippocratic Oath and must answer to a real-life patient (and, potentially, a malpractice attorney), and an insurance executive with a fiduciary duty to maximize profits, I’ll take the physician every day.

But we shouldn’t have to make that choice. I can now imagine a newly designed prior auth system that is ethical, fair, efficient, and relatively frictionless. Most importantly, such a system could increase the odds that patients receive appropriate and cost-effective care.

The advent of generative AI means that such a system is now within our reach. The work of the government, perhaps beginning with Medicare’s new pilot program, is to chart a path that gets us there.

Great article! I also was surprised (kind of) to see Medicare get involved in the prior authorization game. I used to have to fax insurance companies, on behalf of patients, to get approval for coverage of care; so I am definitely glad to see innovation in the space. I guess, I would’ve loved to see CMMI role this out and then from an annual MedPac call, understand the impact.

Thanks for this! The Ochsner example also uses Epic’s Payer Platform - and the results were published in 2022 (before Gen AI!) So it’s both - connecting payers and providers and then also using GenAI to help determine things like medical eligibility.